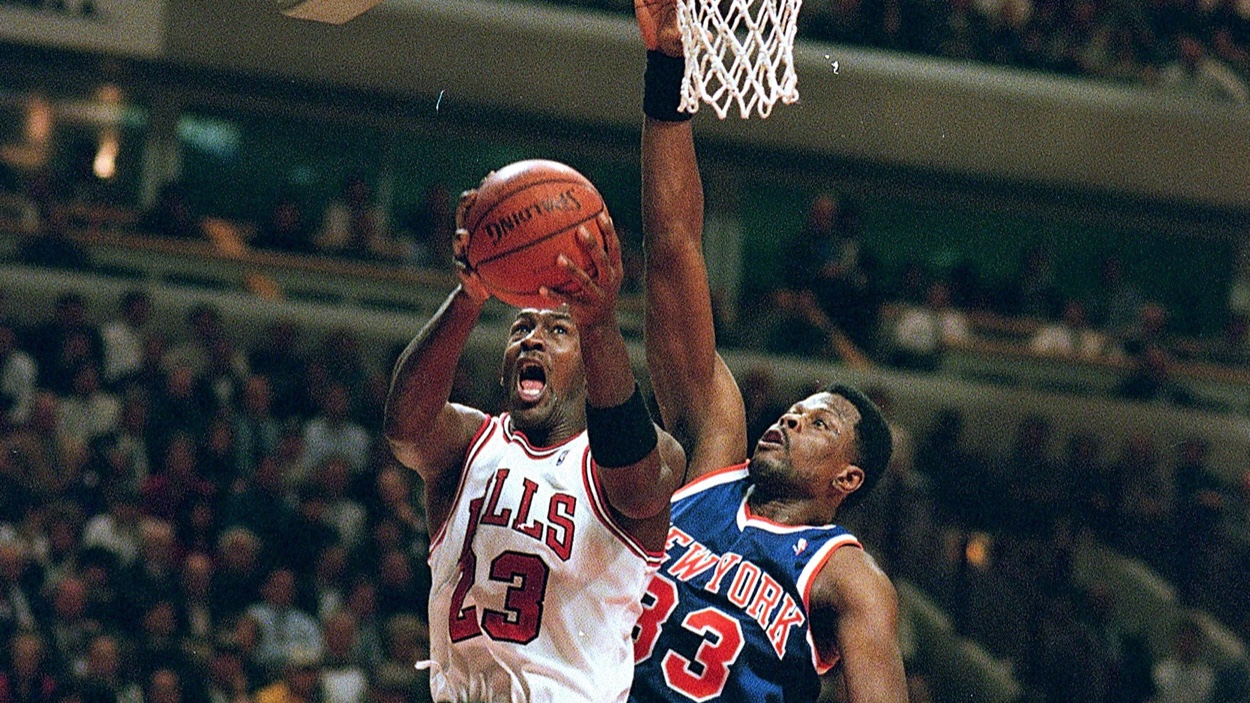

The NBA celebrates NBA 75 roster players almost daily from now until the end of the season. Today’s honoree is Knicks star Patrick Ewing. This column about Ewing originally appeared in the September 30, 2002 issue of The Sporting News.

Patrick Ewing never won an NBA championship. Sing it, memorize it, write it 150 times on the board, tattoo it on your forehead. It’s a fact, and in the twisted web of human opinion, not to mention the even more twisted web of human sports fans opining, that’s all that seems to matter. On the day Patrick Ewing announced that he would no longer play in the NBA, the variety of sports news on the evening news and radio commentary featured the pat on the back followed by the inevitable pat on the back: Pat Ewing? ? Good player, the big one never won.

There are standard arguments that push the boundaries of all sports, and with Ewing’s official retirement, one of the most enduring of those arguments reappears: What good is a great player if he has never won a championship? This is the problem with Ewing, and it’s one NBA fans should get used to. There are a lot of NBA greats from the ’90s approaching reduced bus fare status, and most of those guys will be retiring without league-issued jewelry. This is just a by-product of playing in the same decade as Michael Jordan and the Bulls, but it means that when Karl Malone, John Stockton, Alonzo Mourning and Reggie Miller hang out over the next two years, there will be as much discussion about their failure at win championships as your achievements on the court.

It starts with Ewing, who has obviously had a Hall of Fame career. But when, as I heard a radio speaker put it on Ewing’s retirement day, “the experts have the final say on Ewing in the annals of the NBA, his legacy will always be that he never won it all.” This is the stupid kind of comment. that really burns my sushi.

It’s simple: Ewing is one of the top 10 centers of all time, and that’s a great achievement. After Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Moses Malone, Hakeem Olajuwon and Shaquille O’Neal, Ewing fits comfortably in the second tier of all-time centers.

It’s bad enough that we think of gamers in terms of how the “experts” will portray things in the “annals” (What experts? Where are these annals? What the heck is a legacy, anyway?), But Why are fans and media colleagues immediately looking for a way to detract from the achievements of the big players? Why do many fans in New York think of Ewing in terms of what he didn’t do (that is, he won it all) rather than what he did while playing for such a dispersed organization, one that was lousy in previous years? Did he come, one that failed to surround him with good talent in his prime and one that went through eight coaches in his 15 seasons with the Knicks?

People who think Ewing’s Knicks were worthless because they didn’t have a ring should think about how useless they would have been without him, or how useless they have been since he left. People who think that a player’s only measure is championship rings should remember that Randy Brown has three rings, while Mark Madsen and Mike Smrek have two. People who think that any season that doesn’t end with a championship is an eight-month loss should spend less time kneeling in their Red Auerbach shrines and joining the rest of civilization.

Ewing’s stats are flawless for a center. In his career he averaged 21 points and 9.8 rebounds. Consistency was his trademark, and few players drew as much of his talent as Ewing did. He played hard, he played hurt, and often did so without diminishing production. For eight consecutive seasons, he averaged at least 22 points and 10 rebounds, while missing just 18 games and averaging 37 minutes per game. He averaged 2.4 blocks in his career and, surprisingly, is the Knicks’ all-time leader in steals.

However, remove the stats because anyone who has seen Ewing must acknowledge his greatness and dominance, even without the ring. He was almost unstoppable crossing the lane. He wasn’t a great passer, but keep in mind that, for most of his career, he didn’t have anyone on his team who deserved a pass. As effective as he was in the paint, his ability to knock down 15-foot jump shots (can we call those high-arm jump shots jump shots?) Set him apart from most 7-footers. He was a fierce defender, a warrior and, despite what many maintain, a winner.

There were failures in New York, sure, and they were made worse by Ewing’s championship promises. But failures are the product of expectations, and the only reason the Knicks had high expectations during Ewing’s career was because of Ewing. The Knicks could never find a good complement to Ewing, that perimeter player who could balance Ewing’s inside offense.

Patrick Ewing was good, but he never won The Big One. We can say the same for Malone, Stockton, Miller and Mourning, and surely many will. Hopefully the annals have more to say than that.